Table of Contents

ToggleUnveiling Sub-Clinical Hypothyroidism

Sub-Clinical Hypothyroidism (SCH) remains a pivotal, yet often undiagnosed thyroid disorder. It manifests when TSH levels rise while T3 and T4 remain normal. This silent health challenge affects many, often without their knowledge, warranting significant attention due to its potential health impacts.

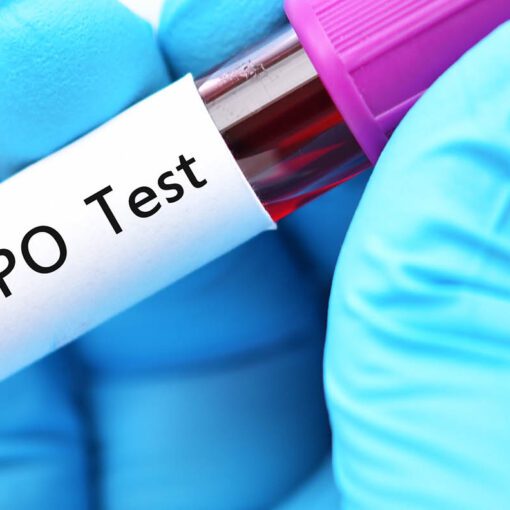

Decoding TSH

Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone (TSH), produced in the pituitary gland, is a crucial indicator of thyroid function. It regulates thyroid hormone levels, and its elevation suggests alterations in thyroid activity. Accurate SCH diagnosis hinges on assessing TSH levels.

Understanding TSH

- Function: Regulates thyroid hormones

- Production Site: Pituitary gland

- Indicator: Elevated TSH signals thyroid changes

Identifying Symptoms of SCH

SCH’s elusive symptoms often make its diagnosis challenging. Typical signs include fatigue, weight gain, and mood swings. Yet, these symptoms can be misleading, necessitating regular screening, particularly for certain high-risk groups.

High-Risk Groups for SCH

- Women, especially post-menopause

- Elderly individuals

- People with a family history of thyroid issues

The Subtle Signs

Recognizing SCH symptoms early is crucial for timely intervention. These include mild fatigue, slight weight changes, and minor mood variations. Often overlooked, these subtle signs can significantly impact well-being.

Symptom Comparison

| Symptom | SCH Patients | General Population |

|---|---|---|

| Fatigue | Mild to moderate | Rarely noticeable |

| Weight Changes | Slight fluctuations | Stable |

| Mood Swings | Minor changes | Not commonly linked |

Comprehensive Health Implications of SCH

Untreated SCH can lead to severe health issues, including heart disease, infertility, and mental health problems. The risk of progressing to overt hypothyroidism is significant.

Impact on Heart Health

SCH notably affects heart health. Elevated TSH levels can adversely affect cholesterol levels and heart function, increasing the risk of heart diseases.

Key Points: SCH and Heart Health

- Cholesterol Levels: TSH elevation can lead to high cholesterol.

- Heart Function: SCH may impact heart rhythm and overall function.

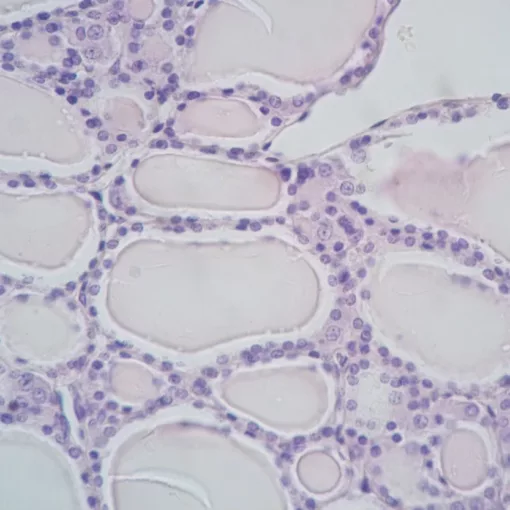

Diagnostic Journey of SCH

Accurately diagnosing SCH involves a multi-step process. It starts with evaluating symptoms and medical history, followed by comprehensive blood tests to measure TSH, T3, and T4 levels.

Interpreting Test Results

Deciphering thyroid function tests is intricate. SCH is indicated by TSH levels above the normal range, despite normal T3 and T4 levels. Regular monitoring is essential to track thyroid function changes and guide treatment decisions.

Personalized Treatment Strategies for SCH

Treatment for SCH varies based on individual needs. Some require monitoring, while others might need thyroid hormone replacement therapy aimed at normalizing TSH levels.

Emphasizing Lifestyle Changes

Diet and exercise have a profound impact on managing SCH. Stress reduction techniques also play a significant role.

Lifestyle Modification Checklist:

- Balanced Diet: Focus on iodine-rich foods and avoid goitrogens.

- Regular Exercise: At least 30 minutes daily.

- Stress Reduction: Yoga, meditation, or other relaxation techniques.

Key Takeaways:

- SCH, a subtle yet significant thyroid disorder, requires comprehensive understanding and regular monitoring.

- Early detection, personalized treatment strategies, and lifestyle modifications are key in managing SCH effectively.